How to Make Beef Production Better on the Environment

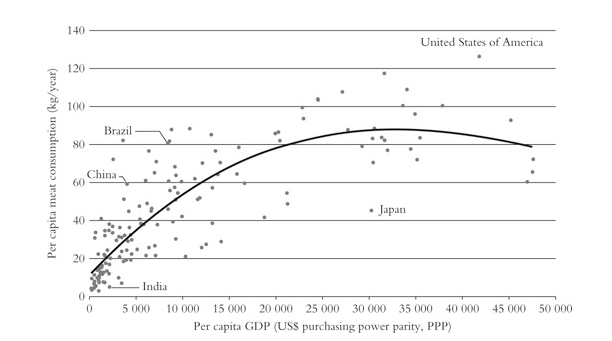

We started out this series past asking if meat can be sustainable (yep, merely we should eat less), and if meat can be moral (perchance not, although that doesn't seem to convince people to give it up). But no matter how we respond these questions, people effectually the world will continue to eat meat. In fact, meat consumption is increasing around the world equally countries become wealthier.

U.N. Food and Agriculture System statistics equally presented in I Billion Hungry: Can Nosotros Feed the Globe? past Gordon Conway

That leaves us with the applied meat question — that is, the question most probable to make a departure in practice: What's the best fashion to produce all this meat?

When I put this to U.C. Davis brute scientist Frank Mitloehner, he gave me a simple respond: We should produce meat as efficiently as possible. Mitloehner is working on the United nations project to appraise the bear upon of livestock on the environs. (The last U.N. study on livestock was hugely influential, but also criticized for overestimating the climate touch on of cattle).

Mitloehner helped hammer out precise rules for doing a full lifecycle assessment on the environmental footprint of animal products. And when he runs the numbers he gets the same answer over and over again: "What is directly linked to meat'southward footprint is efficiency. When production per beast goes up, emissions go downwardly. That has profound impacts," he said. "Profound impacts."

[grist-related-series]

Efficiency is often preceded by the word "ruthless," considering achieving it in ane regard often means sacrificing everything else. Mitloehner is simply talking most producing more meat with less resources. Only of form, if you lot take the pursuit of whatsoever kind of efficiency to its farthermost, it can become ruthless efficiency — and different people accept various opinions about where that line lies. (For more on that, here'south 1 fauna welfare expert'due south accept on modern farming.) Only in this piece, I desire to focus tightly on the environmental impact of meat — and when you do that, it does brand a lot of sense to attempt to produce more with less.

To show how this works, Mitloehner took the example of dairy cows. The boilerplate dairy cow in California produces xx,000 pounds of milk a year. Simply the average dairy moo-cow in United mexican states produces only 4,000 pounds of milk a year, while in India it'due south just 1,000 pounds. The difference comes from better feed, better veterinary care, and amend genetics. If Mexican and Indian cows were similar California (bovine) girls, they would produce the same amount of milk with way fewer animals, which ways mode less climate impact.

Equally cattle geneticist Alison Van Eenennaam notes in Sustainable Brute Agronomics:

The US dairy cattle population peaked in 1944 at an estimated 25.half-dozen 1000000 animals with a total annual milk production of approximately 53.one billion kg. In 1997, dairy cattle numbers had declined to 9.2 million animals and total almanac production was estimated at lxx.8 billion kg.

We've gotten rid of more one-half the dairy cows while increasing milk product by a third. This extraordinary accomplishment means that there are fewer cows producing less methane, while more than Americans are pouring more than milk over their cereal. The carbon footprint of American milk is 63 percent lower than in 1944, researchers have calculated. Nicolette Hahn Niman, in her volume Defending Beef, crunched the numbers for the residue of the livestock in the U.S. and found evidence of a (more small-scale) overall decline: "[E]arly-20th-century farms and ranches had 76 million cattle and 164 million large animals, today they take 68 million cattle and 141 million big animals. In total, that'due south a 14 pct reduction in big farm animals."

Some of this reduction is the result of stock animals, which in one case supplied farmers with their main source of kinetic free energy, beingness replaced by internal combustion engines. Take stock animals out of the equation and the numbers are basically flat. Still, that's remarkable given that our meat consumption more than quintupled in that time.

All this provides some hope that the world could feed the ascent middle form, with its hunger for meat, while too reducing the greenhouse gases produced by agriculture — especially if people in the richer countries cutting their meat consumption. Unfortunately, that's not what's happening, said Ermais Kebreab, a scientist who studies greenhouse gas emissions from livestock. "The fashion things are going, developing countries basically have more and more animals with the same level of efficiency, and I think that's not corking for the environment, or for the producers," he told me. "The best manner to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and degradation of the surroundings is to meliorate efficiency. If they could have more efficient animals, the farmers would make more than money."

Some improvements are distinctly depression tech. It makes a huge departure when farmers simply go along the animals with the well-nigh desirable characteristics for breeding, rather than selling them, Van Eenennaam said. But when farmers are very poor, they often have picayune choice only to sell the animals that volition bring in the highest cost: "They sell the big ones and keep the trivial ones for their breeding stock," she said. It's only the opposite of what you lot'd want.

Kebreab, who has worked the last five years with small farmers in Vietnam, constitute that farmers could significantly reduce their emissions and improve efficiency with a few uncomplicated changes. For case, farmers ofttimes end upwardly with too much rice straw, which they burn, he said. By treating that harbinger with urea, they tin make information technology digestible for ruminants, he said.

Another simple manner to improve efficiency is to supplement ruminant feed with a little grain at key points in the animal's life, like during pregnancy, Kebreab said. When a cow is eating grass, about seven percent of the free energy from that feed turns into methane, but on a feedlot, only 3 percentage of the feed free energy turns into methane — the rest goes into meat or milk.

This may require a fleck more than explanation, since we more often than not think of grass feeding as the preferred system. Information technology's clearly greener, in terms of state utilise, to have ruminants only eating grasses, or residues (like rice harbinger), that don't compete with man nutrient crops. Simply it'southward also clear that cattle produce more greenhouse gases — and abound more than slowly — when eating only grass. Giving cattle grain for a few months is a good environmental pick, Mitloehner told me.

"All but a small-scale percentage of beefiness cattle are on pasture nearly of their lives, and then fattened up on a feedlot for the last iv months on average," he said. "On grass information technology takes them 26 to 30 months to reach marketplace weight. On feedlots information technology takes 14 to xv months, [10 months on grass and] the terminal iv months on a diet of fourscore to ninety percent corn."

There are greenhouse gas emissions associated with growing and transporting that corn, just those are typically smaller than the emissions that come from a steer eating grass and burping up methane for an boosted 10 months.

Another relatively low-tech mode to make meat product more efficient would be to farm more than fish — if we include fish in the definition of meat. Fish are just incredibly efficient. Considering they are cold-blooded and buoyant in the water, they don't burn down free energy generating rut and fighting gravity to move around. (For greater — oceanic! — depth on the potential of fish farming, run into Amelia Urry's piece in this series.)

Every expert I talked to said that higher-tech improvements would besides make a huge difference in decreasing the environmental impacts of meat. As long as we are talking almost fish farming, we should notation that a genetically engineered salmon can produce a pound of fish for every .83 pounds of feed it eats — which seems to violate the 2nd constabulary of thermodynamics. (Information technology doesn't, because the meat includes water weight — that's standard for calculating feed conversion ratios — still, information technology's astonishing relative to other ratios.)

When I asked Van Eenaaman where we might detect low-hanging fruit, she suggested working on disease resistance. "Nosotros lose 20 percent of animate being protein to illness," she said. "I think genetics is the best way to work on that because once you have the disease resistance in there it'southward inherited and it's free to the offspring."

Improving disease resistance could be accomplished through conventional breeding or factor editing, and it would accept several benefits, Van Eenaaman said. "You're not treating them with antibiotics, they are healthier, so welfare improves, you aren't spending coin on handling, and you improve efficiency."

One of Kebreab'south favorite high-tech solutions is a genetically engineered squealer. Pigs are terribly inefficient in the style that they absorb phosphorus, he explained. When plants take upwards phosphorus, they lock information technology in a sort of molecular condom — phytic acid. Unlike ruminant animals, pigs do not produce the enzyme phytase — the key that unlocks this safe. This creates problems on both ends: Pigs just keep eating until they are able to excerpt enough phosphorus from the grains; and you lot can only apply and then much pig manure to a field before you overload the country with phosphorus. In China, which already has half the world'southward pigs and a growing ambition for pork, people are drastic to observe a solution to phosphorus pollution, he said. And at the aforementioned time that hog country is saturated with the stuff, the globe is running out of phosphorus.

"Phosphorus is a finite resources — when it's done, it's done," Kebreab said. "Correct now pigs apply 30 to xl percent at most of the phosphorus in feed, and and then the balance would exist excreted. Nosotros have genetically engineered pigs that produce the phytase enzyme — they apply 80 per centum of the phosphorus."

But, he said, scientists are worried nigh the reaction to genetically modified animals, and the industry worries that eaters will observe GM animals less flavory than GM crops.

"That'southward what frustrates some of us," he said. "In that location is a solution for an environmental problem, just we aren't using it."

When I asked Kebreab if he had a vision for the future of animate being agronomics, he also came upward with something that might either be low-tech or high-tech, depending on how you look at it. "Nosotros demand diversity," he said. "The environment, it's quite different in different places. For case, dairy cattle demand about xv degrees Celsius — that's their thermoneutral zone — and if you have them in hot and humid areas they're not going to practise well. To me it doesn't make sense to take animals in environments where they are not suited. Instead, specialize in different areas — working with nature instead of trying to change nature all the time."

"Interesting," I said. "Then in that case, working with nature ways more international trade?"

"Yeah," he replied. "That could be a solution for sure."

All of this was a flake of a mind-bender for me. Just as information technology was counter-intuitive to think of grass-fed beefiness being more carbon intensive than grain-finished beef, I'k used to thinking of local food being greener than the kind shipped from another climate. But every scientist I talked to assured me that the carbon costs of producing meat inefficiently usually outweigh the carbon price of transportation. "The way these demands can exist met is through college efficiency," Mitloehner said. "I don't think there is whatsoever other fashion."

Of course, the other fashion is to not meet the demand for meat. Some people accept talked about the idea of taxing meat to squelch the demand, but that's withal just a concept, and even if a meat tax passed (probably in some wealthy country) it would probably only make a minor blip in the worldwide consumption trends. As long equally people continue to farm animals and eat meat, it makes environmental sense to produce that meat as efficiently equally possible.

It may non make sense in other ways: Feedlots are a lot less aesthetically pleasing than grasslands. Once we expand the field of view from a narrow focus on the environment, we might desire to trade efficient production for amend creature welfare, or a farming system that empowers the little guys, or farms that improve the view rather than spoiling it.

The researchers I talked to were focused on what could be done on a grand scale, affecting the entire world. Just at that place are minor-calibration examples of people producing meat in a way that seems to remainder out all those things nicely. I liked the wait of Paul Willis' grunter farm when I visited it — this Niman Ranch performance isn't as efficient equally most modern squealer farms, but it'south certainly a lot prettier. And glory farmer Joel Salatin is every journalist'southward favorite proof that it'south possible to produce a lot of meat on a small amount of country. I bet if anyone ever did a full scientific assessment of all Salatin'due south ecology impacts he'd come up out looking pretty good.

Small scale, intensively produced meat might be the best choice for people who can beget information technology. But there are billions of people who can't afford it, or just don't care, and they're buying more than meat every year. That hungry majority is going to buy meat, whether information technology's environmentally friendly or not. Increasing the productivity of animal agriculture, especially in the poorest parts of the world, will practise a lot to reduce the impact of all the meat eating, while too rewarding farmers.

Source: https://grist.org/food/the-practical-case-for-producing-meat-more-efficiently/

0 Response to "How to Make Beef Production Better on the Environment"

Post a Comment